Women's Rights

Emergence of Women Rights

"Private ownership of property is vital to both our freedom and our prosperity."

-Cathy McMorris

WOMEN'S POSSESSION AND RIGHTS ON THE LAND AND THE PROPERTY STATED IN THE INTERIM CONSTITUTION OF NEPAL, 2063 AND IN PRACTICE: AN ANALYSIS

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION OF THE STUDY

1.1. Background

In many countries around the world, social norms and customs limited the women’s land and property rights and hampered their economic status and opportunities to overcome poverty. The issue is important for the rights of women because ownership of land and property empowers women and provides income and security. Without resources such as land, women have limited say in household decision-making and no recourse to the assets during crises.

Rights to land and property include the right to own, use, access, control, transfer, exclude, inherit and otherwise make decisions about land and related sources. Debates on gender equality gained much discussion in the last three decades through the three world conferences on women (Mexico, 1975; Nairobi, 1985; and Beijing 1995) and intermittent international conferences. These conferences of women's rights largely established the international agenda for equal rights on the inheritance property and rights of the land. International documents, for instance, the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) has clearly focused on the rights of women.

The first United Nations International Conference on Women (Mexico, 1975) and the declaration of the International Decade for Women had a slogan of equality, development and peace. The aim of the slogan was to establish gender equality all over the world. This subject is the issue itself firmly appeared on the agenda for women's equality.

Usually, people acquire property through inheritance, through marriage settlements and via public policies of redistribution. Most women through social relations acquire property. The acquisition of property through redistributive public policies does not have the same effects for women and men. Let us take the issue of land rights. In many parts of the developing world, the land has been and continues to be the most significant form of property in rural areas. Agriculture is still the most important source of livelihoods, and the ownership of land is the single most important source of security.

The economic resources under the control of male heads of households do not necessarily translate into well-being for women and children. Thus, independent ownership of such resources by women, especially land, can be critical in promoting the well-being of the family and the empowerment of women. Yet, action by states to redress the class, caste and race imbalances in the control over land has rarely addressed the issue of gender imbalances. Thus, land reforms in Nepal have virtually kept women out of the reckoning.

The contemporary struggle over the land rights is a burning issue of Nepal. Many reports present that the gender equality and women empowerment are catalysts for multiplying development efforts. Thus, investments in gender equality yield the highest returns of all development investments.

Women usually invest a higher proportion of their earnings in their families and communities in comparison to men. A study shows that the likelihood of a child’s survival increased by 20% when the mother controlled household income. Increasing the role of women in the economy is part of the solution to the financial and economic crises and critical for economic resilience and growth. However, at the same time, we need to be mindful that women are in some contexts bearing the costs of recovering from the crisis, with the loss of jobs, poor working conditions and increasing precariousness.

Some critics define property as righteous while others as the central instrument of social regulation. For many, women are sometimes denominated as the sub-human category and dehumanized in cultural and moral aspects. According to Adorno, The totality of mass culture culminates in the demand that no one can be any different from itself.[1] Despite stern criticism, it is uncertain, that the women have been restrained and suppressed by means of tools from the historical reference.

The property, in the past, used to refer to the different forms. When people began to acquire the forms of property, women fell into prey as the form of property. Sometimes, a woman ceased to be a separate legal personality when she married. In the course of time, she is able to possess the property even if she is widowed or divorced. In history, a princess possesses the state or a part of the state after the death of the king as ownership or dowry.[2]

In some cultures, a woman obtains the property after marriage and the death of her husband and parents. A transfer of property typically accompanied it between the two families. In many parts of Asia, the bride's father provides a dowry, a gift of cash or the property to his daughter or to her husband.[3] A Madhesi community of Nepal also transfers some property to the daughters as dowry. Although Nepalese laws are women friendly, women do not have full rights on the land and the property in practice. As a result, a mother cannot transfer her land to a daughter as gratuity or gift (bakas) without the consent of her sons in practice. A buyer also hesitates to buy the property because of partition disputes.

1.2. Research Problems

The research problems of this paper will be as follows:

i) Whether the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063 and the Muluki Ain, 2020 have adequately able to eliminate discrimination on the land and the property rights in practice for women in Nepal or whether women have enjoyed the equal rights on the land and the property in practice addressed in the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063.

ii) Whether the international treaties accepted and ratified by Nepal as a State Party can help to grant or transfer the land and the property by the women in practice in Nepal.

1.3. The Objectives of the Research

The objectives of the research are:

i) To trace out how the male dominance has existed in practice on the land and the property that makes disparity on equal rights in Nepal and,

ii) To know how the culture depresses the women to achieve the land and the property rights in practice.

1.4. The Significance of the Study

The research has focused a general concept of the ownership of land and property of female in Nepal. The study has analyzed the rights to land and property for women in practice and in the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063 compares with the international instruments. Moreover, this study has also explored some strengths and challenges of the Constitution relating to land and property rights and has recommended for overcoming the challenges.

This thesis can be useful for the parliamentarians, policy makers, judiciaries, and government agencies. Academicians, lawyers, students of law and human rights, activists of human rights, civil societies, trainers, INGOs/NGOs and those who are interested in this subject also may benefit by reading the research.

1.5. Limitation of the Study

This study is limited to the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063, Muluki Ain, 2020, some international instruments and treaties about equal rights on the land and the property regardless sex, color, caste, and gender. Importantly, this research is prepared for a requirement of LLM degree. Unfortunately, to abide within the limitation of words, the research cannot cover detailed and comparative studies of the rights of the land and the property.

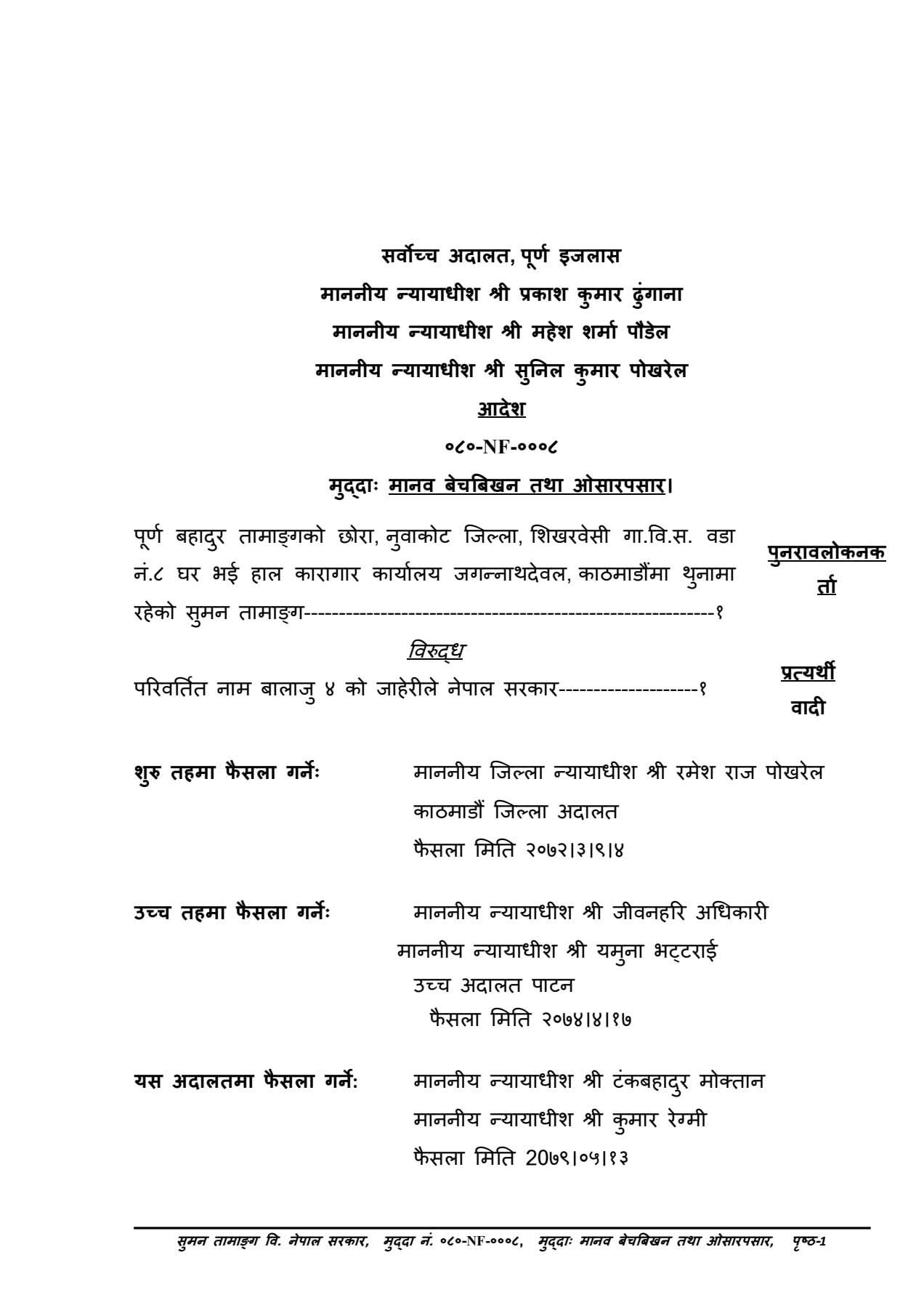

Moreover, this research has focused on how women have not obtained equal rights of parental and personal property in practice as stated in the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063, and with the provisions of CEDAW and other international documents. The researcher has concerned some cases decided by the Supreme and other Courts of Nepal about the land and the property rights. It has also analyzed the trend and jurisdiction of the Nepalese and international system.

Besides, this dissertation has tried to explore not only lacunae of the Constitution and the Acts but also positive aspects as well. Finally, this study will try to provide some suggestions and recommendations.

1.6. Organization of the Study

The approach of the dissertation is descriptive and analytic. Concerning to the limitation of words and time, I have applied the doctrinal method for the source and information.

The first chapter of the dissertation is about the introduction with justification, objectives, and significance. The second chapter deals with the brief overview of the literature and some specific movements that concentrate on the property rights. The third chapter relates to the research methodology in terms of design, sources of data, and its nature, the technique of collection and method of presentation. The fourth chapter reveals the concept of the land and the property rights for women, its definition and efforts at the international level. The fifth chapter concerns with various conventions and legal provision of land and property rights. The last chapter concludes with the analysis and recommendations.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Numbers of literature relate to the property rights, however; the researcher attempts to deal comprehensively with the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063 that has prescribed women's property rights in various chapters. Although the thesis has highlighted to the present constitution of Nepal, the evaluation and analysis of the following documents will be noteworthy.

2.1. Women's Roles in Economic Development[4]

The land and the property rights are basic elements of people from the time when they began to know the value of assets. Notably, the rights of the land and the property for women remained a valuable and prosperous in society. Many right activists and others state the ownership of land and property to establish a fair society. In this sense, Boserup states in her book that women’s property rights are fundamental to women’s own economic security as well as wider economic development.[5]

In terms of equality, women’s land and the property rights are debatable issues in social and legal paradigm. Here, many critics have tried to explain whether property rights have been conferred in Hinduism, Christianity or in Islamic regions. Yet, many people in the world are unaware of the rights granted to women by religious laws mostly in Islam. Free ownership of the land and the property rights to trade, buy, or sell is a chief component of Islam. It is stated that Islam has provided clear-cut strategies for empowering women to enhance their status, and to add to the social and economic well-being of society.[6] Therefore, the land and the property rights in a simple form, in different religions and societies are still important.

Concerning to the importance, the property is not only a natural right, but it was developed and recognized in society by efforts of people. Rousseau speaks, "No citizen shall be rich enough to buy another, and none as poorly as to be forced to sell himself"[7] The politically guaranteed right to property is distinguished from natural possession, and is not a right to unlimited accumulation. Precisely because of ‘the force of circumstance always tends to destroy equality, the force of legislation ought always to tend to preserve it. This response reflects Rousseau’s conviction that even well-constituted states are always subject to corruption, and cannot survive indefinitely.

2.2. The Ancient Ethics: A critical introduction[8]

In this book, Resniik B. David, the political and sociological thinker, advocates women's property rights that are absolute values. He believes that people bind up human dignity and worth with the human capacity to choose moral values and lives. He has studied critically about the human condition and focused on the deteriorated situation of women due to inefficient property.

Critic, Susan Sauve Meyer has critically stated on the rights of the property within morality and ethics. She trusts and values of property significantly through the observation of social and political exercise in the ancient Greece. Although, women sometimes faced some of the challenges in acquiring the rights of property, through the philosophical writings and religious activities granted them to posses the property as males. She elaborates concerning the rights in her book The Ancient Ethics that:

"As city planners, quite naturally concerned with ensuring that the citizens will be adequately supplied with the human goods. The ‘great benefits’ they supply to the citizens include the human goods. These include an adequate food supply, sufficient private property, and honor as reflected, for example, in funeral rites and interactions between generations." [9]

Whatever concerns, the value of property was not greatly regarded to the Stoics because they did not concern anything as a matter. Most of the social regulation had greatly influenced to the philosophical dimension. Here, the writer further states, "In addition, the Stoics claim that it is natural for us to pursue health, property or wealth, strength, beauty, good birth and friendship as well as freedom from pain and to pursue these things in a community."[10] It proves that the right to property, despite gender, was greatly enumerated in the ancient Greece. Like Aristotle and Plato, the Stoics agree that human beings are ‘political animals’ but they are equipped with the aid and need of material and earthly life

In the beginning, the right to property for women became controversial for a political and philosophical thinking. Many people, especially the feminist thinkers were in favor of property rights while patriarchal societies were not in favor of it. In 1989, Charlotte Perkins Gilman noted that the unique attribute of the female economic position is her economic dependence. Agreeing with Mill she contended that a woman must possess economic means outside of the control of her husband in order to have an independent economical status.[11]

2.3. Becoming Human: The Origins and Development of Women's Human

Rights

In this book, Fraser S. Arvonne has critically analyzed on the property rights of women tracing to the historical movements, writings, and contemporary documents. She concerns to the philosophical writings to legal provision. Quoting to a book "The Subjection of Women" she explains:

"As John Stuart Mill argued the question is whether women must be forced to follow what is perceived as their natural vocation, or whether, in private and public life, they are seen as the equal partners of men. While the division of spheres, based on sex and known as patriarchy, may have been justified as a necessary division of labor in the early evolution of the human species, the system long ago outlived its functionality and has been challenged by women, and a few men, since, at least, the fifteenth century."[12]

The writer has stated that without property rights women would dissolve and such scatter leads various types of problems. He further quotes the types of difficulties lead various types of insults, physical intimidation, vandalism, theft, and others. It is also stated that the right to have property has become a significant concern in the eyes of equality.

2.4. Civic Republicanism[13]

Although the concept of property has been defined in various terms, it is closely connected with the power. Generally, politics, power, and property are interconnected in some degree. In her book, "Civic Republicanism" the writer argues that politics, power, and slavery are interconnected with the property. Women were concerned with the assets of property even in the development phase of ancient Greece. Relating to the property rights, Iseult Honohan debates in her book Civil Republicanism,

"Politics was marked by power struggles between the classes and among politicians who championed their different interests. Freedom was still understood in opposition to slavery, but expressed as a status guaranteed by law rather than as equal rights of political participation. A more extensive and impersonal system of law to which property was central covered all citizens, and was applied by professional lawyers and jurists."[14]

The property, even to the women, is an essential part of self-estimation. Here, Honohan defines property as the guideline for women. He further quotes that, "They should be able to own property, work and take up professions; in this way, they will contribute to society, and make men more independent also; ‘if women are not permitted to enjoy legitimate rights, they will render both men and themselves vicious to obtain illicit privileges. "[15]

In the 1830s, States passed laws and statutes that gradually gave married women greater control over the property. New York State passed the Married Women’s Property Act in 1848, allowing women to acquire and retain assets independent of their husbands. This was the first law that clearly established the idea that a married woman had an independent legal identity. The New York law inspired nearly all other states to eventually pass similar legislation. To upgrade the property rights, the State should concern further way. Most importantly, the Party States and ratified nations should make a wide concern for the protection of any name violation. "Having ratified CEDAW and under its own constitution, Pakistan is obliged to treat women equally and to protect their fundamental human rights."[16]

2.5. The Ethics of Science: An Introduction [17]

In this book, Resniik B. David, the political and sociological thinker, advocates women's freedom and individuality that is absolute values. He believes that people bind up human dignity and worth with the human capacity to choose moral values and lives. For this, the human condition should be focused on the deteriorated situation of women who are mostly financially disrupted.

In this book, the writer states that without some common standards, societies would dissolve and such scatter leads inferiority to the women. He also quotes that when women are dispersed in the mainstream of property gaining, they violate science’s principles of mutual respect and opportunity; they undermine cooperation, trust, openness, and freedom in science. In the last two decades, a property right has become a significant ethical concern in science as more women have entered the scientific profession.

When men and women will be calculated in different perspectives, the issue becomes serious a point of criticism. As men and women are known equal parts of a coin, they should not be discriminated because of any type of inequality. The writer further quotes that women’s property rights violations are not only discriminatory, they may prove fatal. For instance, effects of disparities in relation to unequal inheritance or property rights on women are envisaged to be deep-rooted in their life cycle in various aspects which have impaired their overall self-development as well as their capability in a family, a community and national development.

The need for equality of inheritance and property rights should be recognized in all parts of the world. The control of the means of production is a source of economic and political power. Where men retain such control by the exclusion of women from inheritance, inequitable inheritance rights perpetuate inequitable economic and political power within communities. This is particularly so in the agricultural and rural communities, in which the land furnishes the principal means of production.

Therefore, the impact on the overall development of women can address only by the equal rights. The lack of equal inheritance and property rights for women has disabled them in various fields.

2.6. Historical Introduction to English Law [18]

The book presents author's concerns over types of violation, especially in terms of gender bias that can dehumanize the women in equal status. For this, especial traces of law and practical exercises are straightly needful. In this, he separates gender and its discrimination. The book illustrates that gender-based inequality is incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person, and must be eliminated. This can be achieved by legal measures and through national action and international cooperation in such fields as economic and social development, education, safe maternity and health care and social support this mean overall development is necessary to achieve women’s dignity.

Furthermore, English law defines the role of the woman that they should be equal to the man. Upon marriage, the husband and wife became one person under the law, as the property of the wife should not hand over to her husband, and her legal identity does not cease to exist. Any personal property acquired by the wife during the marriage should have full rights. After years of advocating, the book also presents that the women’s property has been addressed their own property. After this, the wives' legal identities were also restored, as the courts were forced to recognize a husband and a wife as two separate legal entities. Further, married are able to hold stock in their own names

2.7. Property Rights: An Issue in Nepalese Context [19]

The author of this book has explored and analyzed women's rights to equality in property in Nepal from a jurisprudential perspective. This book has also analyzed the judgments of the Supreme Court (SC) of Nepal in relation to women and justification. Similarly, the book has presented the impact of a defective value system, and women’s rights in a right-based approach such as women’s property right, marital rights, right to health and reproduction, right to civil and political participation, right to access to fair justice, violence against women and girls, migration and trafficking in relation to Nepali legal provisions and international instruments.

The book, under the chapter of ‘Women’s Property Rights’, has dealt the definition of the rights of property in Nepal, international instruments related to the violence against women and the Nepalese legal framework to deal the problem of discriminatory law on the property rights of women. The author has also pictured the situation of the property shared among women in Nepalese society.

This book, however, has not updated with new amendments of law in relation to women's right, the literature has helped the researcher to understand the women's rights in Nepalese context and concept of violence against women.

2.8. Property Renders to Women in Mahabharata[20]

The women in Hindu culture exercised their right over property in the past. It is expressed that, "The right to property in Hinduism was greatly rendered from the Vedic tradition. However, some traits and customary practices denied the women as a protector of property. It’s deeply rooted in Hindu society as a woman is under guardianship."[21]

Women, however; politically diverted and they were asserted as the property of powerful persons, they were highly enumerated by their social activities. Many critics exert that although, women in the Vedic period were powerful and inherited equal rights in property, the rights in the Mahabharata period lessened.

The book further expressed that the women had limited rights, as a daughter she had no right in father’s property. Each unmarried daughter was entitled to one-fourth of patrimony received from her brothers. After the death of the mother, her property equally divided into sons and unmarried daughters. A wife was entitled to one-third of her husband’s property when he was alive. After the death of the husband, she was supposed to lead an ascetic life and had no share in her husband’s property.

2.9. Women’s Rights in Islam and Somali Culture[22]

This report is prepared by ‘The Academy for Peace and Development Hargeysa, Somaliland’ in December, 2002, under the guidance of UNICEF. A reader can find the overall situation of Somali women from this report. For instance, it presents culture, economic status and rights to property of Somali women. In general, the report reveals the socioeconomic situation in a clear way. Similarly, the workshop discusses and concludes with conception and definition of discrimination, equality before the law, enjoyment of property rights, access to service and loans of Somali women, cultural barriers in property possession and violence against women.

Further, the workshop discussed with various references that the Islamic religion is positive to women from the past. For instance, one can see the justice and equality during the16th century in Mughal India of Akbar, one of the powerful Kings of Indian sub-continents who justified the rights and property of women. He banned the child marriage and opposed the Hindu's rejection of widow remarrying. "On the inheritance of property, Akbar noted that in the Muslim religion, a smaller share of inheritance is allowed to the daughter, though owing to her weakness, she deserves to be given a larger share."[23]

Additionally, "Quran accepts the property rights of women as she is liable to receive the free gift of their marriage portions. Stated that "And give the women (on marriage) their dower as a free gift; but if they, of their own good pleasure, remit any part of it to you, Take it and enjoy it with right good cheer."[24] Likewise, "From what is left by parents and those nearest related there is a share for men and a share for women, whether the property is small or large,-a determinate share."[25]

Islam further quotes that a Muslim cannot bequeath more than one-third of his or her total property. However, if a woman has no blood relations and her husband the only heir, then she can will two-thirds of her property in his favor. Similarly, a woman is entitled to inherit property as a daughter, widow, grandmother, mother, or son’s daughter.

In addition, the workshop presents that the nationality of any Muslim is the Islamic Doctrine (Aqida Al-islaamiya). Islam through marriage aims to assure greater financial security for women. They are entitled to receive marital gifts, to keep present and future properties and income for their own security. No married woman is required to spend a penny from her property and income on the household. Generally, a Muslim woman is guaranteed support in all stages of her life, as a daughter, wife, mother, or sister. Inheritance in Islam is based on kinship.

Many scholars such as Imam Shafi'i[26] hold the view that it is obligatory that a husband provides a gift to his divorced wife in accordance with the size of his wealth. The Islamic Shari'a recognizes property rights of women before and after marriage.[27] Therefore, it is illegal for a Muslim woman to lose, or to be denied her rights by marrying another Muslim.

CHAPTER III

METHODS OF THE RESEARCH

3.1. Research Design

The design is a descriptive and analytic base under the study of the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063, Muluki Ain, 2020 and some international documents. This research design reveals the work division, engagement, participation, and possession of various fields of women and their estimate earnings and possession regarding to the land and property rights of women in Nepal. It helps in exploring some weak practices despite the Constitution and it recommends in reviewing to equalize and promote the conception in reality.

Undoubtedly, the purpose of the design is to dig out the practice of possession on property as granted by the Constitution, the Act and other international instruments on the land and the property rights for women. The research design is helpful to expose the fact, and to analyze the existing legal framework of the property rights of land and inheritance in Nepal. Similarly, the analytic research design traces the trend of property division, share and documentation in Nepalese context.

3.2. Nature and Sources of Data

The study is on descriptive and analytic method. Kinds of literature are concerned to justify the research. The researcher has made an effort in collecting and reviewing the relevant literature from different sources. The researcher has visited the Land Revenue Office, Dillibazar in Kathmandu to collect the fact information. To find out actual data, the researcher has searched all Land Registration Papers (lalpurja) of a certain time in the office. Apart from the concerned people, various sources like websites, news, TV casts, and other sources are also studied.

3.3. Universe Procedure

A collection of information on the possession of land and property of women throughout the offices of Land Revenue is not possible because of various constraints. It is also not possible to state accurate data by various interviews and records except the Land Revenue Office (Malpot Karyalaya) of Dillibazar. Concerning to the complication, the area of study and information are inserted by certain research, interview and inquires. The research is also a product of various legal documents, verdicts of courts and the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063.

3.4. Tools and Techniques of Data Collection

The researcher has conducted research on doctrinal, questionnaire and interview methods. Descriptive and analytic ways are also concerned. Particularly, the field study and interview are the main source for the research however; the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063 has been the source to compare with practice and reach in conclusion. Similarly, several books, literature, articles, reports are the supportive documents to write the research. The relevant legislation and some decisions on the land and the property rights made by different Courts are also included.

3.4.1. Collection of the Primary Data

To dig out the dissertation, the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063 and International instruments such as ILO reports, CEDAW reports, and so on are studied. More importantly, some related cases of the land and the property rights made by various courts have been studied.

3.4.2. Collection of the Secondary Data

In this study, the researcher has collected and utilized the secondary data from both secondary authority such as books, articles, journals and published/unpublished reports and the primary authority such as laws, conventions. The secondary data are collected from different libraries, published and unpublished reports of different organizations and the internet. Some books of international writers, Acts and documents of international seminars are also important.

3.4.3. Questionnaire and Interview Schedule

The questionnaire and two short interviews help to collect the detailed information of women who have owned the land and the property in the office. The interviews also present the situation of women's participation in money generating field, their position and salary.

3.5. Data Analysis and Presentation

The researcher has analyzed and presented the data in the form of descriptive and analytic ways. To clarify and support the thesis, the researcher has also made a questionnaire and two interviews with the officer of the Land Revenue Office of Dillibazar and the journalist and women rights activist. However, the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063, Muluki Ain, 2020 and international documents are the sources to compare and contrast to relate the land and the property rights of women.

Bibliography

1. Adorno, Theodor W., The Cultural Industry: Selected essays on mass culture, London and New York: Routledge, 2001.

2. Agnes, Flavia, Law and Gender Inequality: The Politics of Women's Rights in India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999.

3. Agosin, Marjorie, Women, Gender, and Human Rights: A Global Perspectivs, London: Routledge, 2005.

4. Bhattarai, Ananda Mohan, The Landmark Decisions of the Supreme Court, Nepal on Gender Justice, Lalitpur: National Judicial Academy, 2010, Ed.

5. Bhattarai, Baburam, Rajnaitik Arthasasthrako Aankhajhyalbata, Kathmandu: Jagadhwoni Publication, 2063.

6. Boserup, Ester, Women’s Role in Economic Development, London: George Allen and Urwin, 1970.

7. Butler, Judith, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex, London: Routledge, 1993.

8. Campbell, Tom, Separation of Powers in Practice, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2004.

9. Carlyle, A.J. Property: Its Duties and Rights, London: Macmillan, 1913.

10. Chaturvedi, Badrinath, The Mahabharata: Criticism and Inquiry in the Human Condition, New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2006.

11. Curzon, LB, Question and Answer Series: Jurisprudence, 3rd Ed., London and Sidney: Cavendish Publishing Ltd, 2001.

12. David, Resniik B., The Ethics of Science: An Introduction, London and New York: Routledge, 2005.

13. Dworkin, RM., Taking Rights Seriously, London: Duckworth, 1976.

14. Fraser, S., Arvonne, Becoming Human: The Origins and Development of Women's Human Rights, Jaipur and New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 2003.

15. Ghimire, Shankar, Property Rights: An Issue in Nepalese Context, Pairavi Prakashan, Kathmandu, 2002.

16. Greenawalt, Kent, Conflicts of Law and Morality, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987.

17. Hidayatullaha, M. and A. Hidayatullaha, Mulla's Principles of Mohammadan Law, Mumbay: NM Tripathi, 1999, Ed., 19th Ed.

18. Honohan, Iseult, Civic Republicanism, London: Routledge, 2008.

19. Hughes, Gerald J., Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Aristotle on Ethics. London: Routledge, 2001.

20. Karki, Tek Bahadur, A Statistical Review of Women's Labor and Employment in Nepal, Kathmandu: Bhudipruan Prakashan, 2012.

21. Khan, Muhammad, The Muslim 100, Leicestershire, United Kingdom: Kube Publishing Ltd, 2008.

22. Kiralfy, A. K. R, Historical Introduction to English Law, 4th ed., Delhi: Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1977.

23. Locke, John, Second Treaties of Civil Government, Chapter IX, Section 222, 1662.

24. Lockwood, Berd B., Women's Rights: A Human Rights Quarterly Reader, Ed., United States: John Hopkins University Press, 2006.

25. Meijer, Marinus J., Marriage Law and Policy in the People's Republic of China, in Chinese Family Law, London: Cavendish, 2004.

26. Menon, Latika, Female Exploitation and Women's Emancipation, New Delhi: Kanisha Publishers and Distributers, 2004.

27. Meyer, Susan Sauve, The Ancient Ethics: A critical introduction, London and New York: Routledge, 2008.

28. Mill, JS, On Liberty, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1906.

29. Padia, Chandrakala, Theorizing Feminism: A Cross-Cultural Exploration, Jaipur and New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 2011.

30. Prasai, Krishna, The Concept of Legal Theory, Kathmandu, Nepal: Human Rights Watch Group Nepal, 2012.

31. Rawals, John, A Theory of Justice, Rev. Ed., USA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

32. Sheila Dauer, Indivisible or Invisible: Women's Human Rights in the Public and Private Sphere, New York: Routlegde, 2003.

33. Sen, Amartya, The Idea of Justice, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009.

34. Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations, Book I, Chapter X, Part II, 1776.

35. Snare, Francis, The Nature of Moral Thinking, London and New York: Routledge, 2002.

36. Thacker, Prabha, Technology, Women’s Work, and Status: The Case of the Carpet Industry in Nepal: Mountain Regeneration and Employment, Discussion Paper Series. ICIMOD, Kathmandu, 1992.

37. Walikhanna, Charu, Women: Silent Victims in Armed Conflict, New Delhi: Serials Publications, 2004.

Web and Software

1. Microsoft, Encarta, Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation, 2008.

2. Vhugen, D.S. et al., ‘Ensuring Secure Land Rights for the Rural Poor in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study’, 2009, www.rd,ap,gov.in (accessed on 26 March 2015).

3. The Hindu, Oct 13, 2005.

4. ILO Report, 2010.

5. ICCPR, Article 2, Part II with Optional Protocols (1966; 1989).

6. National Human Rights Commission, A Status Report, Lalitpur: National Human Rights Commission, Nepal, 2003.

[1] Theodor W. Adorno, The Cultural Industry: Selected essays on mass culture, London and New York: Routledge, 2001, p. 92.

[2] Iseult Honohan, Civic Republicanism, London: Routledge, 2008, p. 90.

[3] Ester Boserup, Women’s Role in Economic Development, London: George Allen and Urwin, 1970, p. 30.

[4] Ester Boserup, Women’s Role in Economic Development, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1970, p. 41.

[5] Ibid, p. 252.

[6] Ibid, p. 253.

[7] Iseult Honohan, Civic Republicanism, London: Routledge, 2008, p. 95-96.

[8] Susan Sauve Meyer, The Ancient Ethics: A critical introduction, London and New York: Routledge, 2008, p. 40.

[9] Ibid, 42.

[10] Ibid, p. 136.

[11] Chandrakala Padia, Theorizing Feminism: A Cross-Cultural Exploration, Jaipur and New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 2011, Ch-6, Dismantling Metanarratives, p. 134.

[12] Arvonne, Fraser S., Becoming Human: The Origins and Development of Women's Human Rights, Jaipur and New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 2003, p. 78.

[13] Iseult Honohan, (n 2). P. 28.

[14] Iseult Honohan, (n 2), p. 30.

[15] Ibid, p. 109.

[16] Marjorie Agosin, Women, Gender, and Human Rights: A Global Perspectives, London: Routledge, Ed., p. 65.

[17] Resniik B. David, The Ethics of Science: An Introduction, London and New York: Routledge, 2005, p. 182.

[18] A K R Kiralfy, Historical Introduction to English Law, 4th Ed., Delhi: Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1977, p. 175.

[19] Shankar Ghimire, Property Rights: An Issue in Nepalese Context, Pairavi Prakashan, Kathmandu,

2002, p. 164.

[20] Badrinath, Chaturvedi, The Mahabharata: Criticism and Inquiry in the Human Condition, New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2006 , p. 185.

[21] Ibid, p. 186.

[22] Prepared by The Academy for Peace and Development Hargeysa, Somaliland, UNICEF, Women's Rights in Islam and Somali Culture, Nirobi, Kenya, 2002.

[23] Amartya Sen, The Idea of Justice, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 38.

[24] Quran, Sura 4.

[25] Ibid,Sura 7.

[26] Al Shafi'i was a Muslim jurist who lived from 767–820 CE.

[27] Muhammad Khan, The Muslim 100, Leicestershire, United Kingdom: Kube Publishing Ltd, 2008, p. 201.